Small gestures.

These are the things Boyah Farah remembers appreciating as he struggled as a teenager to transition from war-torn Somalia to the routine of life in Bedford.

He told a gathering of about 75 people in the Bedford High School library Thursday evening about his memories of his first day as a BHS student, in September 1993. “My counselor and my ESL teacher were waiting for me at the door. And I have never forgotten that. ‘I’m being welcomed? Who am I?’”

Last year Farah wrote a book titled, “America Made Me a Black Man.” One reviewer described the book as “a searing memoir of American racism from a Somalian–American who survived hardships in his birth country, only to experience firsthand the dehumanization of Blacks in his adopted land.”

But both in the book and in conversations during visits to the high school this week, Farah has few negative memories of the three years he lived here with his mother and siblings.

“I feel tonight I’m loved because this is where my journey of writing started,” he told the gathering, which was sponsored by the Parents Diversity Council. He labeled a smile “universal language,” and “when people of Bedford smiled at me, I took that as a welcoming gesture. Tonight, I feel like I’m home.

“I must be in love because I’m back in Bedford where my journey in America began formally. I almost feel like I have to write another book or something because of the emotions of being here.”

Thanks to a rescue organization, in 1993 Farah and his family were transported from a Kenyan refugee camp to a second-floor apartment on Roberts Drive where his older sister was already living with her family.

“My first taste of America was Boston crème” at the Dunkin Donuts near his new home, he said Thursday. “And it’s still there.”

Asked how residents can most effectively welcome newcomers, Farah said, “When you don’t understand the language, it’s tough,” and will take time to overcome. “The best thing that helped me was small gestures of welcome. Smile. Even though they might not understand you, you feel the warmth. These little things will do great things with your life.”

“I don’t remember who gave me money, but I remember people who gave me wisdom,” he commented. “Someone who takes the time and says, ‘Tell me about yourself’ – you never forget that.”

Asked how he learned English, Farah recalled listening to books on audio tape that he borrowed from the library. He also watched a lot of television, including the OJ Simpson trial in 1994, where an attorney used the word “preposterous.” Farah “fell in love with it. ‘Preposterous’ is actually the right word for the life I’ve lived.”

He extended “much love to the wonderful teachers I had here,” and spoke particularly about the influence of Irene Parker, who was Bedford’s METCO coordinator during his years at BHS. “She was the first to teach me what it means to be a Black man in America,” he said, “She took her time and told me, ‘Forget about the culture you had. You will go through what we go through.’ Imagine a kid from a war zone hearing that – don’t spoil America for me. But over the years almost everything she told me came true.”

He continued, “She said, ‘This is what you have to do to prepare yourself’ and gave him a copy of “The Autobiography of Malcolm X.” But I had to go through it. It was wonderful for her to give me access.”

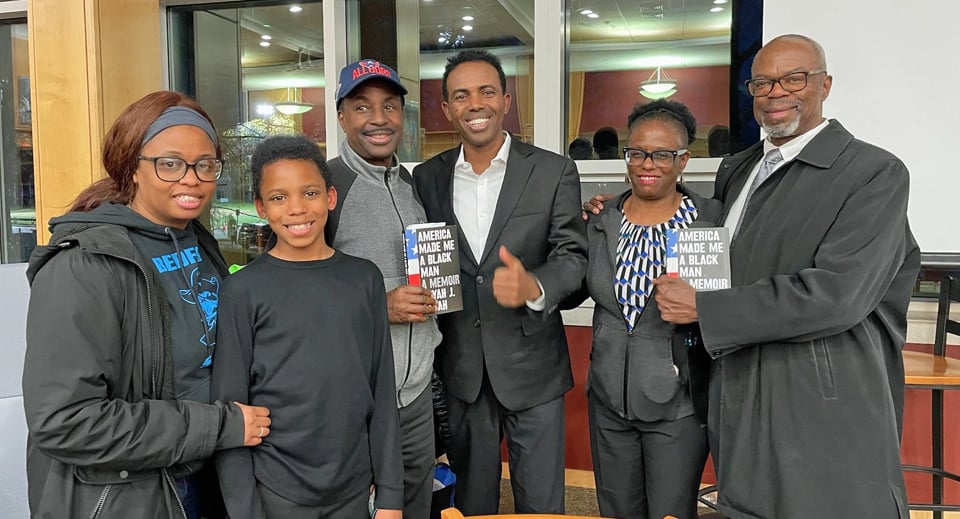

Farah stressed that Parker, who died in 2000, is the only character in his book identified by a real name. Three of Parker’s children, along with a granddaughter and a great-grandson, were present as he said, “Her spirit is in the room.”

Later in the presentation, he said, “When I was writing the book, I was renewing myself: Dear America, Black people love you – and this is who you made me. I want young people to be exposed – the system is what you have to change. If we can do that then America wins because America is each one of us.”

“Systems can be changed by us. That’s how we should think about racism.”

Farah spends most of his time in Somalia; he opened a school there in 2018. Thursday’s program opened with a five-minute video of Farah with a backdrop of the Somalian landscape.

“In Somali custom, you are never a boy. You are always a man in the making,” he said in the recording. After experiencing systemic racism in the U.S., “I had to pick up a pen and start writing. I feel pain and turn that into literature.”

He said in 2017 he was feeling “angry energy. What you do with that energy matters. I decided to write the love letter to America and start the school. The school and writing are how I projected what I had inside.”

“Everything in life prepared me to be a writer,” he said, sharing that his father wanted him to go into medicine. After one science class at BHS, he said, he knew that was not his destiny. “But literature, English, came to me naturally.” He smiled and predicted that he will fulfill his father’s wish by writing a fictional account of his life as a doctor.

The next book will be a work of fiction, Farah said, because “In non-fiction there is no freedom. When you write non-fiction, you overthink a lot. I want to write books that can stay for generations to come.”

“Whatever you project in life, you get back. I want to project love.”